Bonnie Crowds

Exploring the Economic Impact of Tourism Across Scotland’s Iconic Landscapes

the Highlands

Tourism in the Scottish Highlands first gained popularity in the 1840s when Queen Victoria’s visits to Scotland helped promote the landscape, culture, and fashion to a wider audience. Her instant affection for the Highlands, where she sought tranquillity away from royal life, contributed significantly to the region’s appeal, eventually making seaside visits and Scottish retreats a common part of Victorian society. Today, the Highlands draw millions of tourists annually, transforming the region into a major contributor to Scotland’s economy.

The Highlands’ diverse landscapes, historic sites, and cultural richness attract visitors to iconic destinations like Ben Nevis, Loch Ness, the Isle of Skye, and Fort William. This influx of tourists brings essential economic benefits to small businesses, hotels, restaurants, and local artisans, especially those in remote, economically limited areas. Both bustling towns and sparsely populated villages benefit from the capital tourism generates, which, in turn, supports local economies and helps communities thrive despite challenging, often isolated settings.

Old Man of Storr, Portree, Isle of Skye, Highland Council Area

Old Man of Storr, Portree, Isle of Skye, Highland Council Area

Highland Cow, Outer Hebrides Council Area

Highland Cow, Outer Hebrides Council Area

Lighthouse, Island of Bressay, Shetland Islands Council Area

Lighthouse, Island of Bressay, Shetland Islands Council Area

However, rapid tourism growth raises complex questions about sustainability and equitable benefit distribution. While well-developed urban centers can often accommodate high tourist volumes, rural areas may struggle to maintain infrastructure and manage seasonal income fluctuations, creating economic vulnerabilities.

This analysis highlights how tourism shapes the economic landscape of the Highlands, creating both opportunities for growth and challenges. Strategic planning is necessary to balance tourist demand, support sustainable growth, and ensure that economic benefits reach both developed and rural communities. By identifying regions that thrive on tourism and those that struggle with infrastructure limitations, we can work toward a balanced economic ecosystem—one that remains adaptable within the ever-fluctuating tourism industry.

A TOUR OF SCOTLAND

Scotland, a country located in the northern part of the United Kingdom, is known for its historic cities like Edinburgh, its picturesque lochs such as Loch Ness near Inverness, and the rolling hills of Glencoe. Scotland’s unique allure draws millions of tourists each year, eager to explore its breathtaking nature, charming towns, and fascinating heritage.

The country is divided into two general regions: the Highlands refers to the mountainous terrain in the northwest of Scotland, contrasting with the flatter, more urbanized Lowlands in the southeast. This distinction between the Highland and Lowland regions stems from both geographic and cultural differences, with the Highlands known for their rugged landscapes and traditional Gaelic heritage, while the Lowlands are more industrialized.

The Highlands include five council areas with unique landscapes and histories: Argyll and Bute, Shetland Islands, the Outer Hebrides, Orkney Islands, and Highland. Each council area contributes to the region's character and economy, with its own mix of coastline, island life, and wilderness.

The Highland Council Areas

Argyll & Bute

Argyll and Bute is a region in the west of Scotland that encompasses the mainland area of Argyll, as well as a collection of 23 islands. The region is renowned for its landscapes, charming villages, and maritime culture, with popular destinations like Oban, known as the "Gateway to the Isles," and the Isle of Mull, which offers scenic views and abundant wildlife.

Argyll and Bute has played a significant role in Scotland’s heritage, with a rich legacy of Celtic culture, castles, and ancient ruins. The area also supports a thriving tourism economy, particularly for those interested in Scotland's past; however, their biggest industry remains fishing and agriculture.

Shetland Islands

The Shetland Islands, located furthest from mainland Scotland, are known for their dramatic landscapes and Viking heritage. Comprising of over 100 islands, Shetland is famous for its cliffs, beaches, and rolling hills. The islands are also home to notable prehistoric sites and Norse settlements.

Shetland’s wildlife is another major draw for tourists. The iconic Shetland pony, an ancient breed, symbolizes the region's rural heritage. The islands also have a vibrant arts scene with local festivals such as Up Helly Aa.

Shetland’s unique escape, scenic beauty, and outdoor experiences make it a dream destination for those seeking a quieter, traditional Scottish retreat.

Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides, a chain of islands off the northwest coast of Scotland, offer some of the most remote and stunning landscapes in the country. Known for their pristine beaches and rich cultural heritage, the Outer Hebrides are a popular destination for those seeking tranquillity and natural beauty. The islands are home to a unique Gaelic-speaking community and preserved ancient archaeological sites.

Key locations include the Isle of Lewis, known for the Callanish Stones, a prehistoric stone circle, and the Isle of Harris, famous for its breathtaking beaches like Luskentyre and its Harris Tweed.

Orkney Islands

The Orkney Islands, located off the northern coast of Scotland, are a group of 70 islands, with around 20 inhabited. The islands are known for their prehistoric sites, including Skara Brae, a Neolithic village older than the Egyptian pyramids, and the Ring of Brodgar, an ancient stone circle. The Orkney Islands are renowned for their maritime culture, with local festivals, traditional music, and crafts, such as hand-knitted textiles and Orkney wool.

Orkney offers a peaceful retreat for those seeking outdoor adventures, possible Northern Lights sightings, and a connection to Scotland’s unique heritage.

Highland

The Highland Council Area, the largest and most iconic region in the Scottish Highlands, is celebrated for its breathtaking natural beauty, rich lore, and numerous castles. This region offers access to some of Scotland's most famous landmarks, including Loch Ness, the Isle of Skye, and the Glennfinnan Viaduct, making it a prime destination for tourists seeking outdoor adventures like hiking, wildlife watching, and even Nessie spotting.

Overall, the Scottish Highlands offer something for everyone—from stunning historical architecture and ancient, mysterious villages to the natural beauty of mountains, lochs, and coastlines. With such diverse attractions, it's no surprise that the region continues to draw tourists in large numbers. This influx of visitors brings economic benefits, supporting local businesses, creating jobs, and generating revenue across the Highlands. However, in recent years, some council areas have shown signs of struggle in maintaining or growing their tourist numbers, revealing some cracks in the region’s tourism-driven economy.

Tourism is a challenging sector to assess in terms of its economic impact due to its diverse range of industries. The sector encompasses various forms of accommodations, dining establishments, bars, cultural institutions, recreational services, retail, transportation, and more. The complexity in quantifying tourism’s precise economic contributions arises from the indirect impact it can make on various aspects of the economy.

Under Scotland’s Standard Industrial Codes, and for purposes of the data classification in this analysis, the tourism sector includes: hotels and similar accommodations; short-stay accommodations; camping grounds, RV and trailer parks; restaurants and beverage serving activities; tour operator services; museum activities; historical sites and visitor attractions; botanical and zoological gardens and nature reserves; sports facilities; non-racehorse sports activities; amusement parks; and other recreation activities.

Employment in Tourism

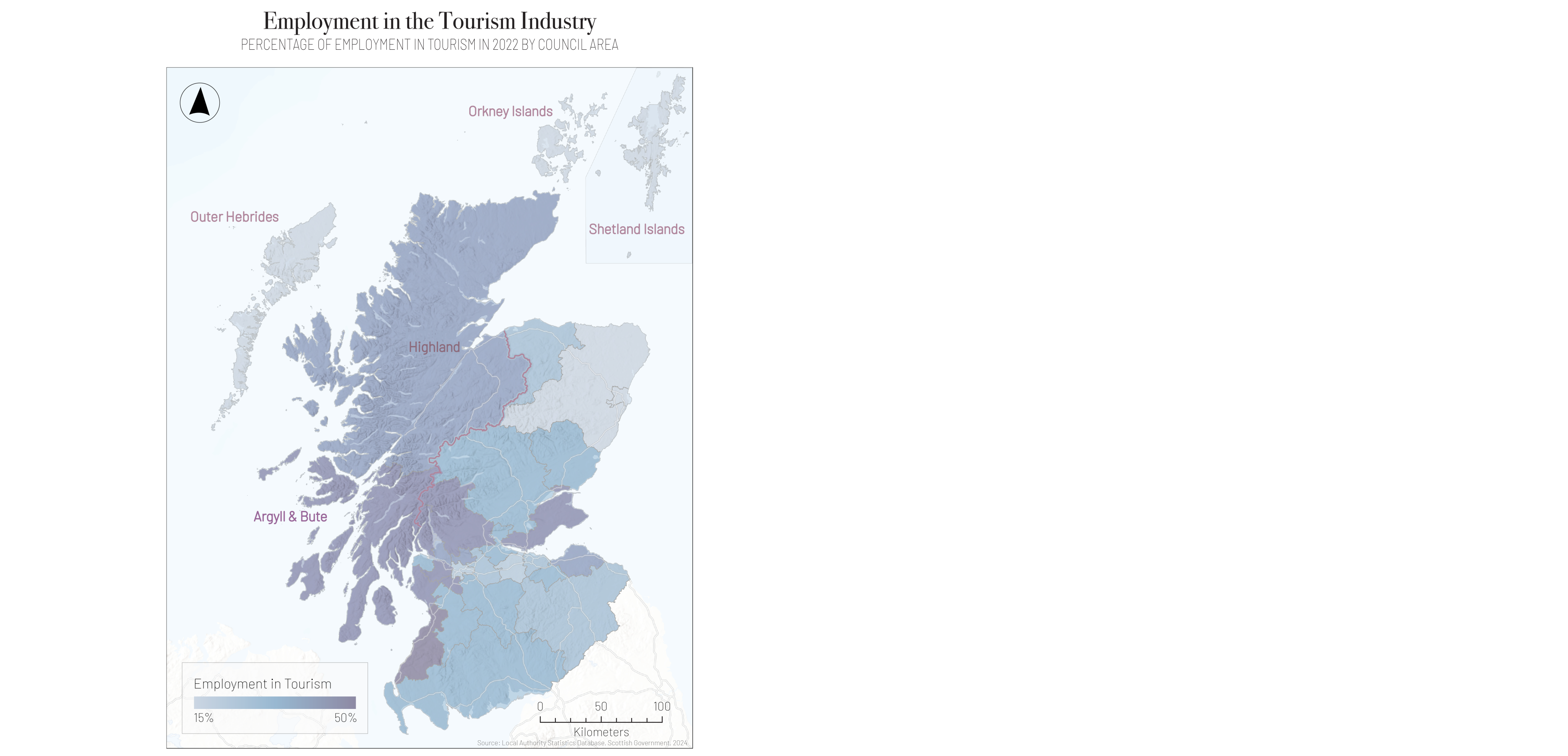

As a whole, the Highlands employs 34% of its workforce in the tourism industry, highlighting tourism's central importance in driving economic activity.

This map highlights the significant dependence of employment and local businesses on tourism across the mainland Highlands. Both the Argyll & Bute and Highland Council Areas have some of the highest employment rates in the country in tourism-related sectors, at 40%, emphasizing the sector's critical role in driving economic activity in these regions. In contrast, the other islands in the Highlands—the Outer Hebrides, Orkney, and Shetland—show a lower reliance on tourism, with roughly 18% of employment tied to this industry.

These differences display how tourism’s impact varies across the Highlands, with some areas deeply reliant on the sector while others remain more diversified. This reliance on tourism influences the local economy and shapes infrastructure demands, making sustainable management essential for long-term stability in these regions.

Revenue in Tourism

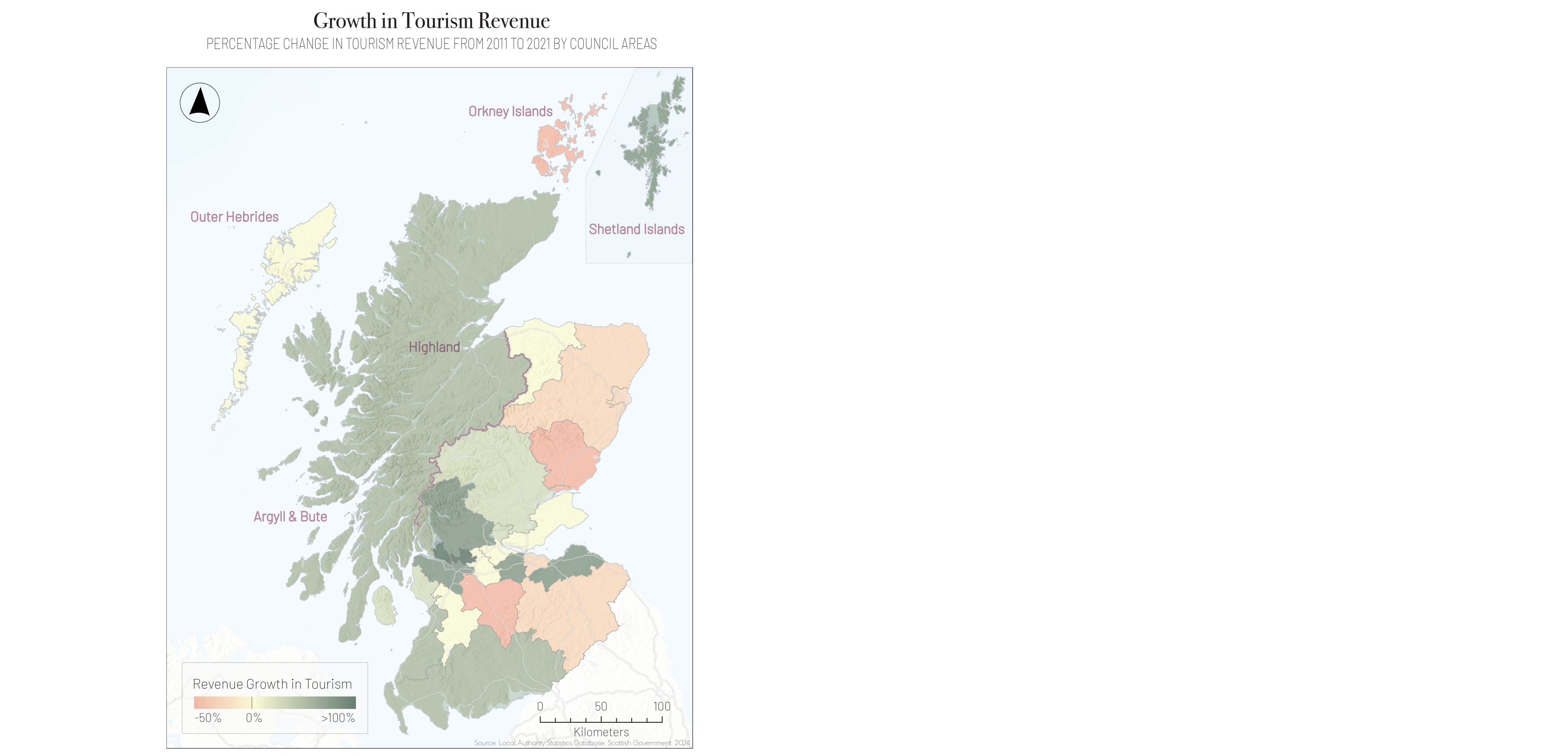

Tourism revenue in Scotland has experienced notable fluctuations, reflecting a volatile and inconsistent pattern over recent years. The Highland and Argyll & Bute Council Areas—regions with some of the highest employment rates in the tourism sector—have shown promising growth over the past decade. The Shetland Islands, while employing less than 20% in the tourism industry, have shown the largest growth in tourism revenue in the Highlands. Conversely, the Outer Hebrides and Orkney Islands have witnessed a significant decline in tourism revenue, highlighting the uneven economic impact across different areas.

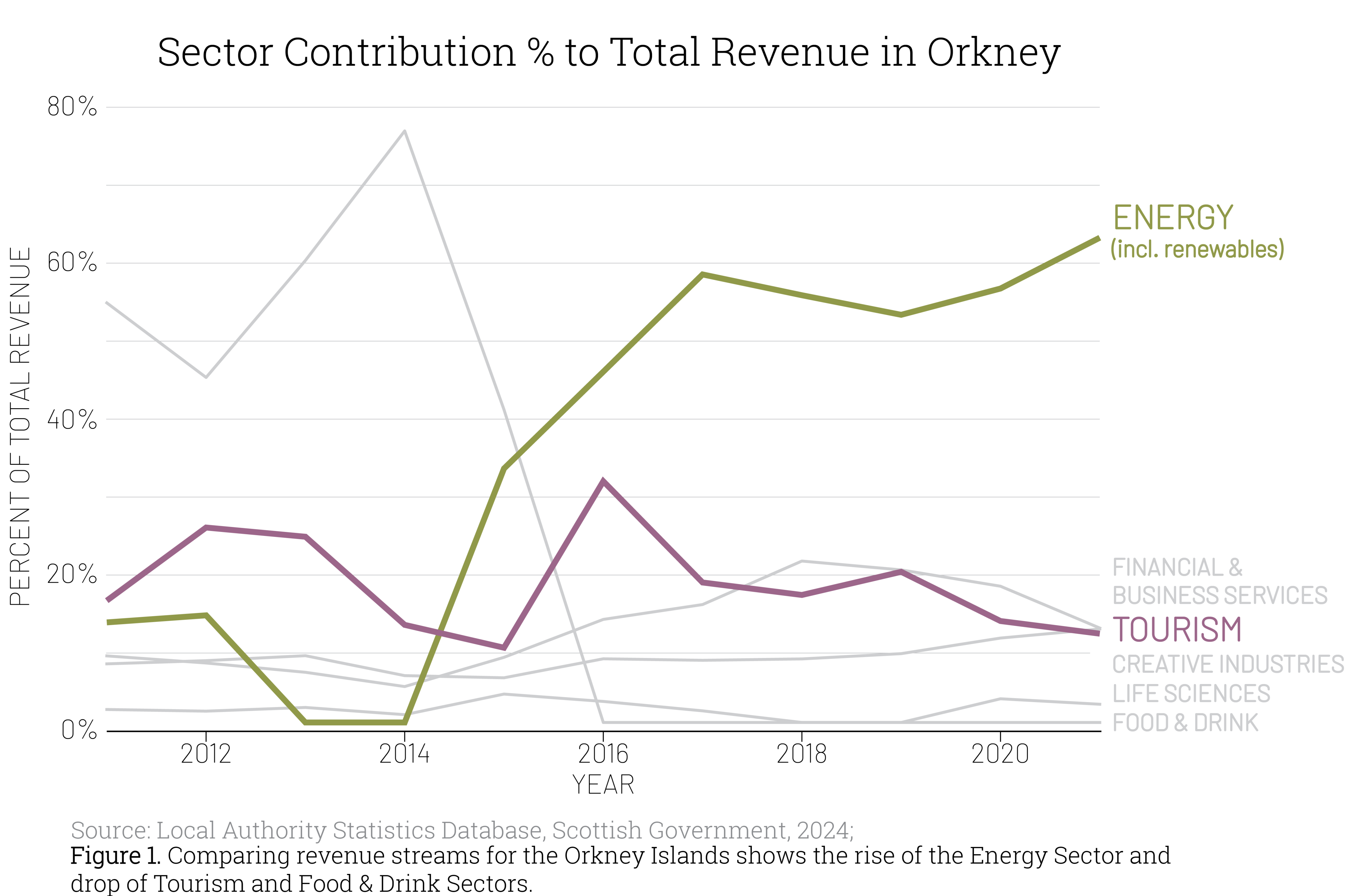

Orkney's concerning decline in tourism revenue has prompted the need to rely on and invest in other sectors. Figure 1 illustrates the latest revenue trends for the region, revealing that while the Food & Drink and Tourism sectors have reduced their contributions, the Energy sector has seen substantial growth since 2014, emerging as Orkney's new primary economic driver. Historically, agriculture and fishing were the dominant industries. With energy now at the forefront, this transition suggests that the sector may offer a more stable and economically sustainable future for the islands.

While the relatively lower levels of tourism in the Highlands' islands are understandable, given their geographic isolation and limited accessibility compared to mainland Scotland, it is noteworthy that these areas have diversified their economic base and sustained themselves through other industries. This resilience demonstrates how local economies, despite tourism's importance, are often supported by a broader array of sectors.

Population Density

Despite the Highlands' significant reliance on tourism, the region is characterized by an exceptionally low population density, with the most densely populated area being Inverness, at around 45,000 people. However, even Inverness pales in comparison to the population densities seen in Scotland's major urban centers like Edinburgh and Glasgow. These cities are located in the dark green "belt" on the map, which represents the most densely populated areas in the country. In contrast, the Highlands' population is widely dispersed, contributing to the region's unique landscapes but infrastructural challenges when accommodating tourism.

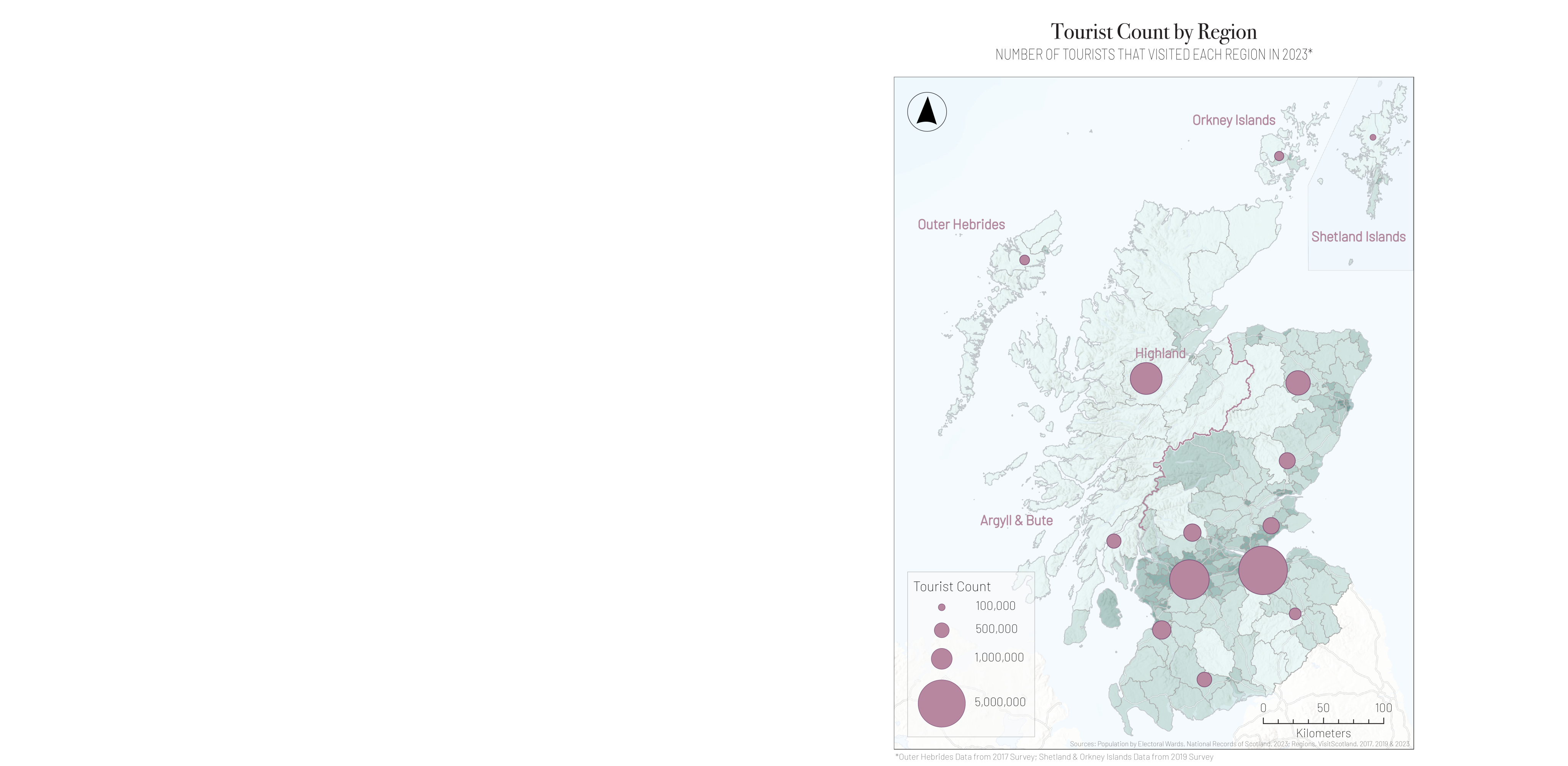

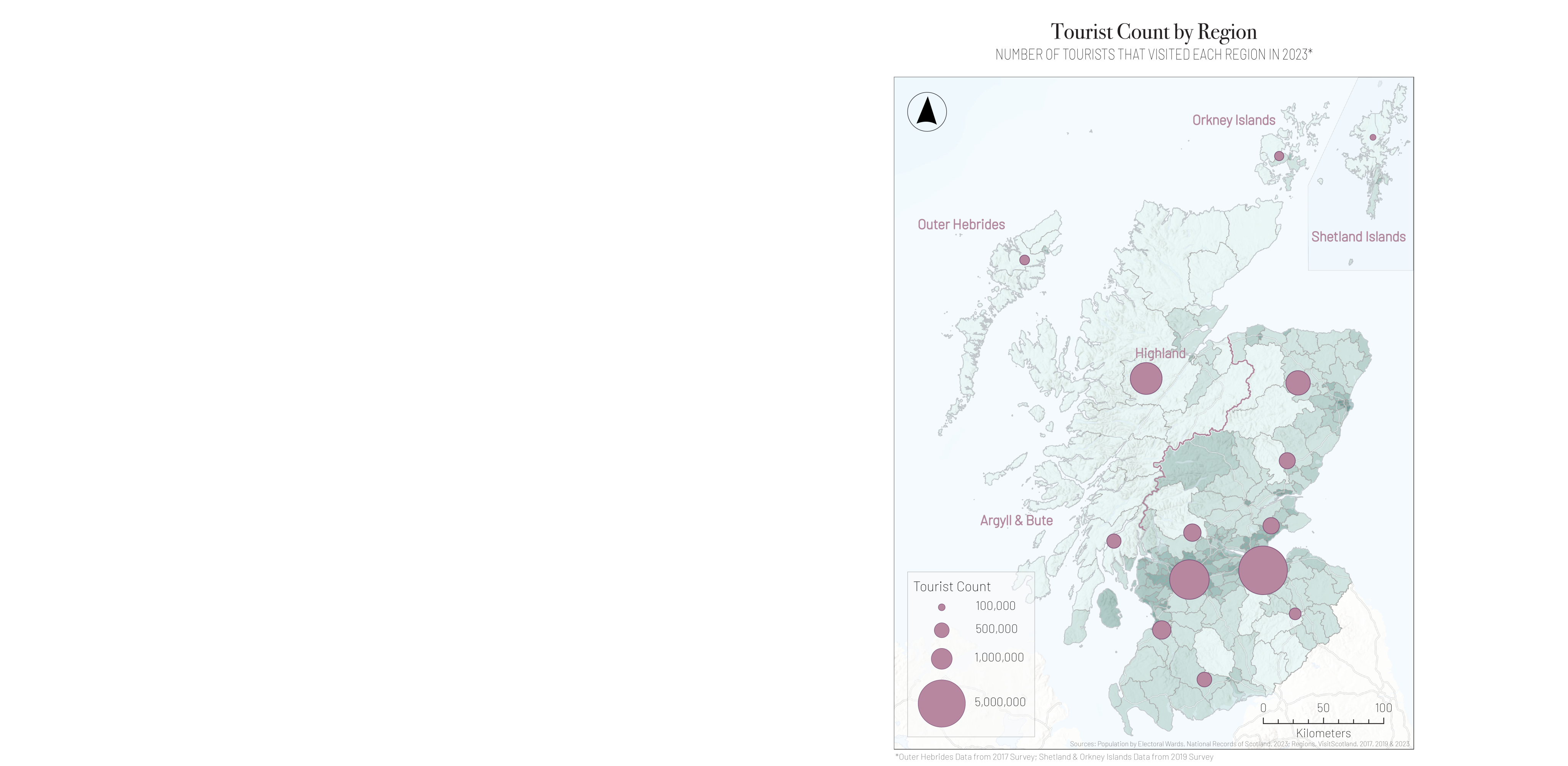

Tourism Count by Region

Tourism trends mirror these population patterns, with the most popular tourist destinations aligning with the urban centers in the central belt—Edinburgh and Glasgow. However, the Highland Council area emerges as the third largest tourist destination in Scotland, drawing considerable numbers despite its relative remoteness. Other regions within the Highlands, such as the Outer Hebrides or Shetland Islands, attract fewer tourists, likely due to their more isolated locations and limited accessibility.

This variation in tourist concentration poses distinct challenges for local infrastructure. High-volume tourist areas like Edinburgh face issues such as overcrowding, strain on transportation networks, and pressure on public services. In contrast, remote areas with rising tourism numbers, such as parts of the Highland Council area, struggle with underdeveloped infrastructure and services. While tourism growth can offer an economic boost, it can also strain local resources, particularly in sparsely populated areas that may not have the capacity effectively to support large influxes of visitors. These complications highlight the importance of strategic planning to balance tourism growth while sustaining local resources and infrastructure.

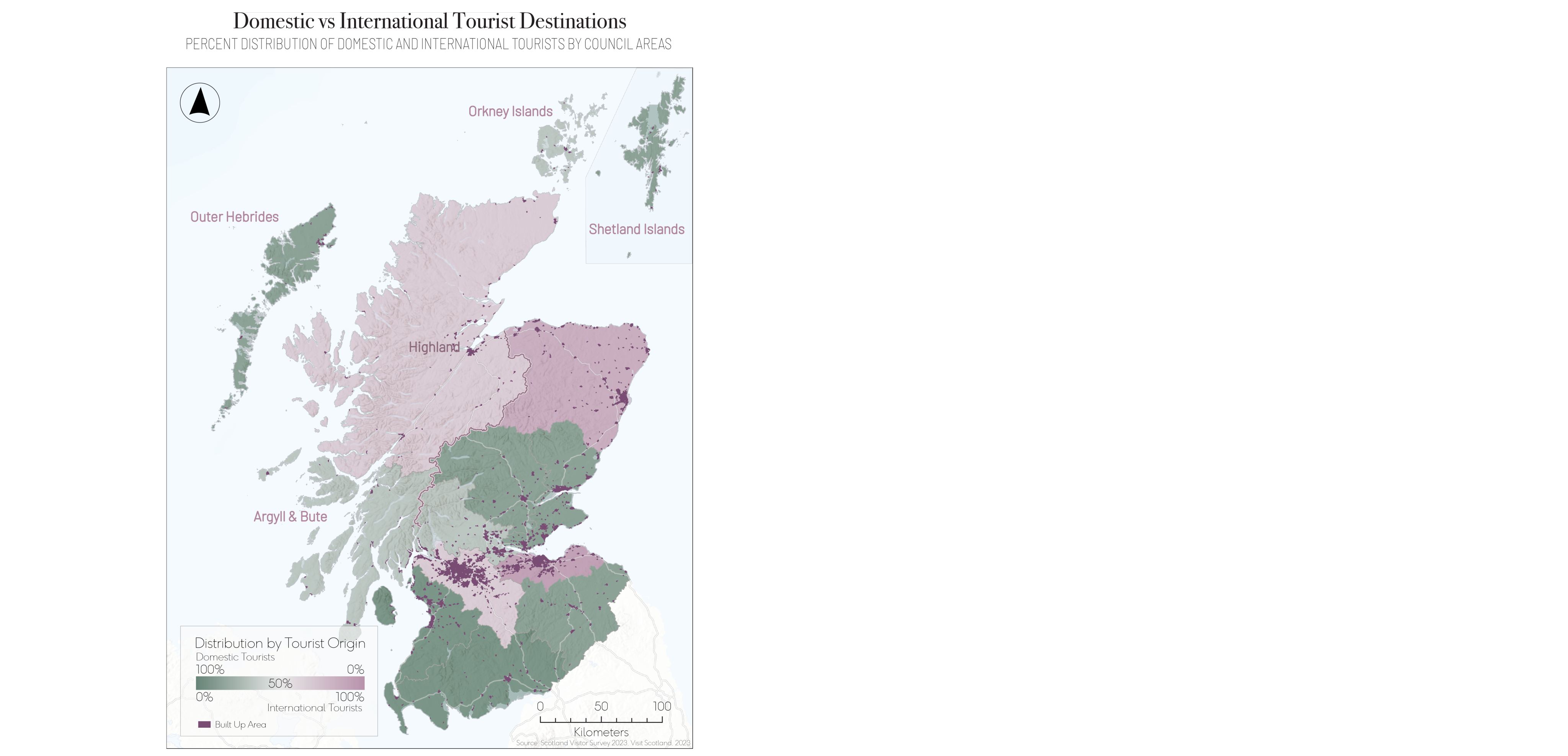

Domestic vs. International Tourists

The distribution of domestic versus international tourists in Scotland has notable economic implications, particularly for the built-up and remote regions. Urban centres are more likely to be visited by international tourists while more remote locations are visited mainly by domestic tourists.

This influx of visitors in urban cities boosts the local economy by driving spending in hospitality, retail, and cultural industries. These cities benefit from a consistent stream of international visitors, which supports a broad range of services and industries.

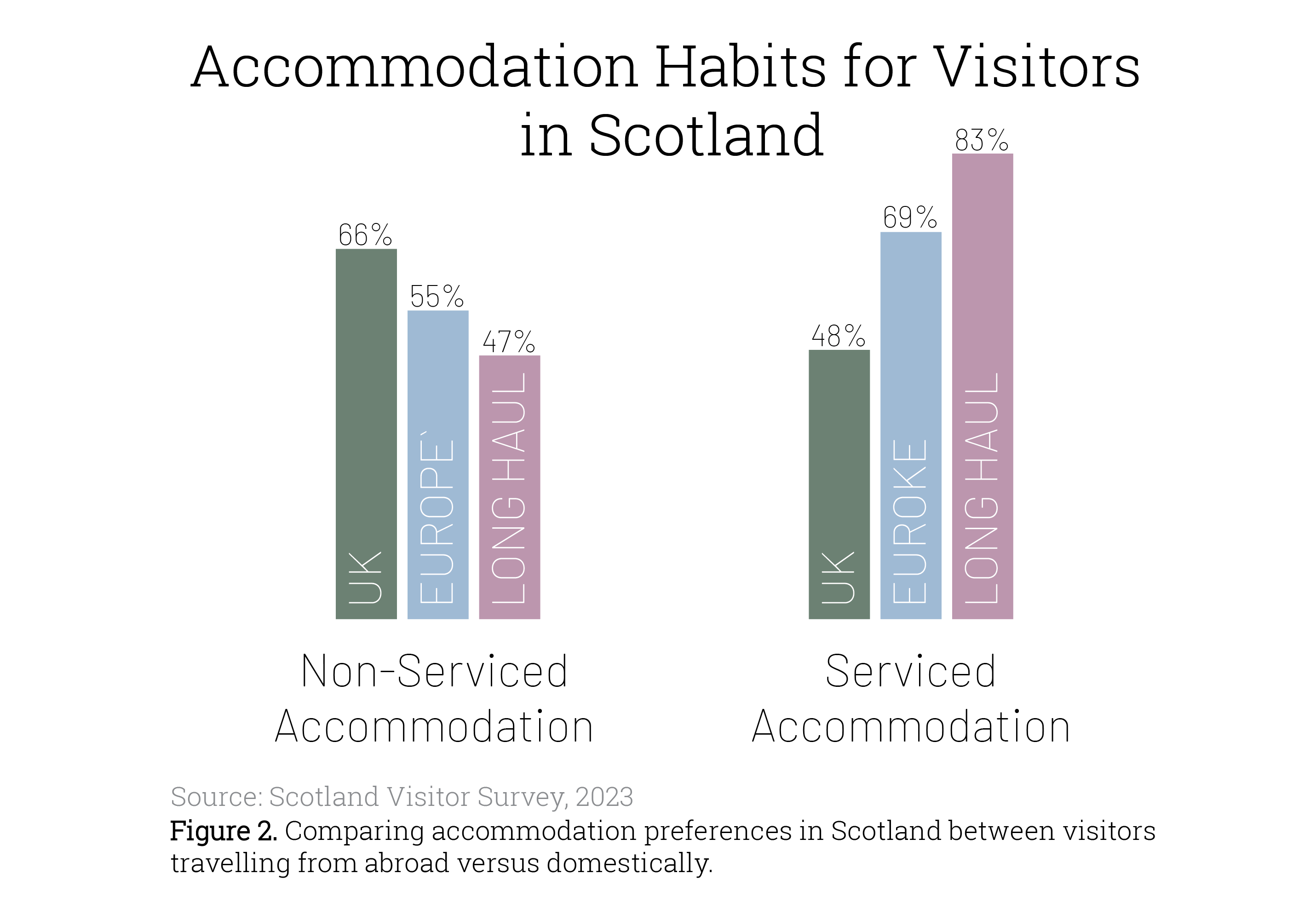

While international tourists typically gravitate toward urban areas like Edinburgh and Glasgow, their preference for hotel-style accommodations, shown in Figure 2, and large-scale infrastructure means that remote regions in the Highlands often miss out on this high-volume, large-scale tourism. However, many of these rural areas may not actively seek such attention, as large-scale tourism can bring both benefits and challenges. Increased numbers of visitors could place strain on local resources, disrupt quiet communities, and even impact the natural environment, which many rural destinations in the Highlands strive to preserve.

In contrast, domestic tourists (those travelling from within the UK) are more inclined to visit the Highlands, particularly rural areas, and favour non-serviced accommodations (fig.2) like self-catering cottages (ie Airbnbs) and camping. This trend not only supports small, local businesses, such as shops and restaurants but also puts less strain on local infrastructure. Non-serviced accommodations require fewer resources, such as water, waste management, and hotel facilities, making them a more sustainable option for rural regions with limited infrastructure. Therefore, Domestic tourism in rural areas contributes to the local economies while minimizing the pressure on facilities and services compared to large hotel groups or resorts.

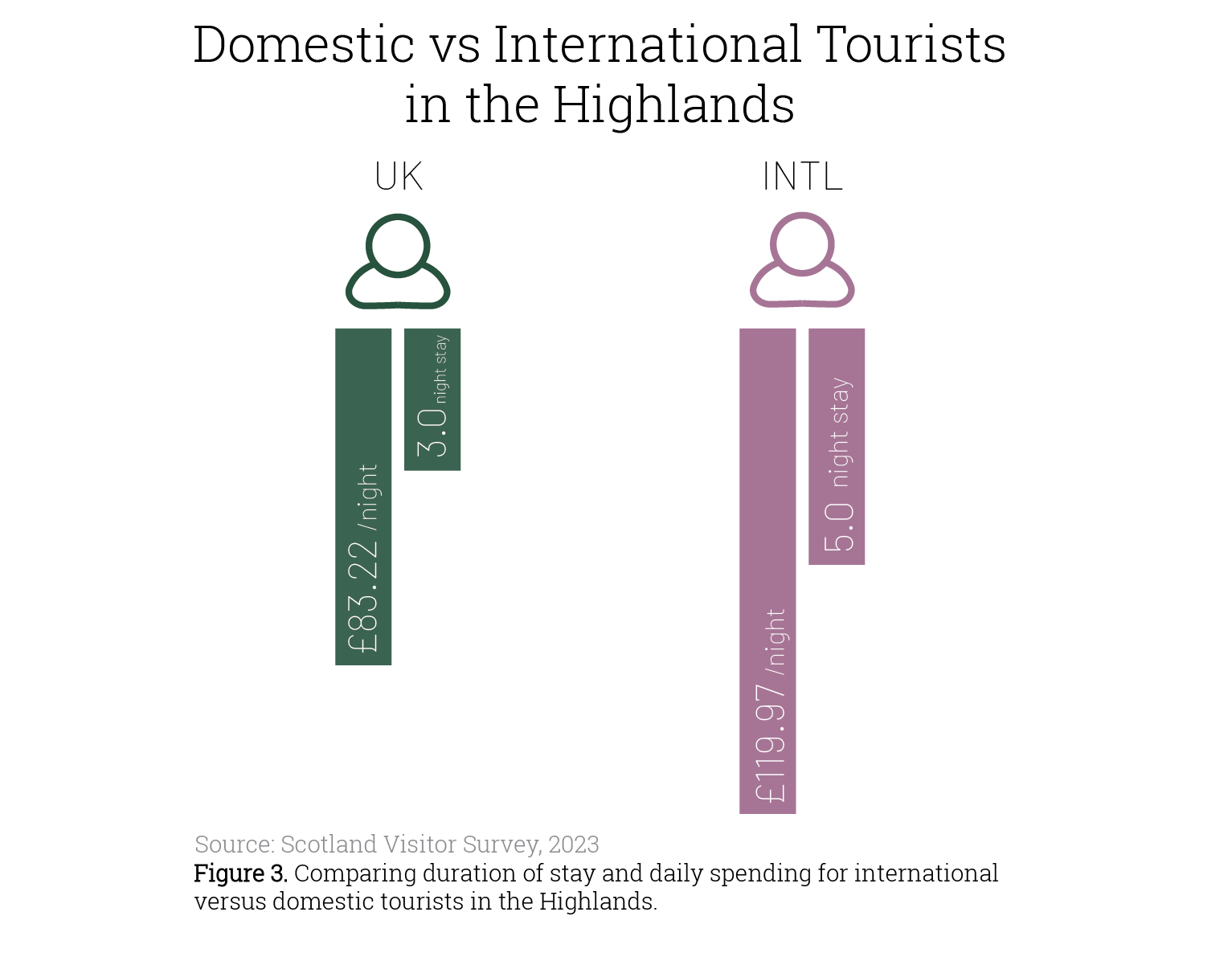

In the Highlands, as shown in Figure 3, the average International tourist spends 30% more than the domestic traveller per night. Although there are 3.5 times more domestic tourists that visit the Highlands every year, International tourists tend to stay longer and spend more per visit.

This difference in tourism patterns—where international tourists typically frequent urban centers, while rural areas are visited more by domestic tourists—highlights how tourism supports both urban and rural economies in different ways. While urban areas are able to offer serviced accommodation and therefore benefit from a more consistent flow of visitors, rural areas thrive from tourism that tends to support local, smaller-scale enterprises and has a lesser impact on infrastructure.

These trends emphasize the need for maintaining a balance between tourism and preservation, key to sustaining both the local way of life and the environment in the Highlands. While these rural regions may be missing out on the financial benefits associated with high international tourist volumes, many may prioritize the preservation of their way of life and the natural surroundings over the pressures of mass tourism.

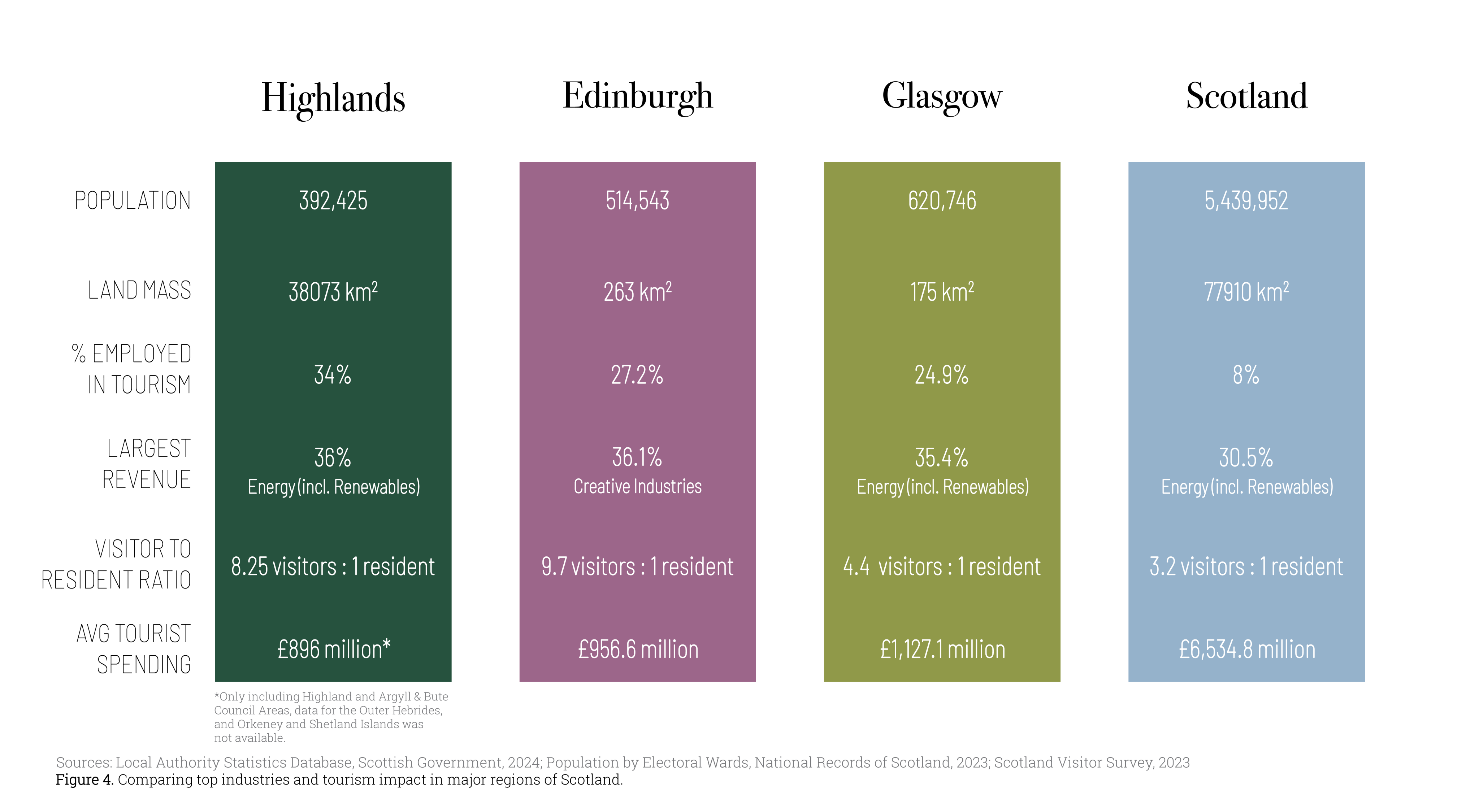

When comparing the Highlands with Scotland’s major tourist hubs in Edinburgh and Glasgow in Figure 4, some key similarities emerge. Although the Highlands employs a higher percentage of its workforce in tourism, its contribution to the country’s overall tourism revenue is comparable to that of Edinburgh. However, tourism is not the largest revenue source for either the Highlands or Scotland’s urban centers. Instead, energy production has become a significant economic driver for Scotland, offering more stability amid tourism’s seasonal fluctuations and aligning with the world’s growing need for renewable resources. Scotland’s ambitious target for renewable energy aims to meet 50% of the country’s energy demand—including electricity, heat, and transport—underlining the sector’s potential as a sustainable foundation for the nation’s economic future.

Additionally, while the two cities are much more densely populated, the Highlands sees a similar visitor-to-resident ratio to that of Edinburgh (fig. 4), accentuating the immense tourist appeal of the region's natural attractions. Edinburgh, with its extensive infrastructure, is better equipped to handle both its dense population and a high influx of tourists. The Highlands, in contrast, face significant infrastructure limitations. This high tourist density, relative to its population, highlights the economic opportunity and pressure tourism brings to the Highlands, emphasizing the need for sustainable development to support this demand without overwhelming local resources.

Orkney Islands

Orkney Islands

Shetland Ponies

Shetland Ponies

Oban, Argyll & Bute

Oban, Argyll & Bute

In summary, tourism plays a crucial role in the economic landscape of the Scottish Highlands, yet its impact varies significantly across regions. The mainland Highlands, especially council areas Argyll & Bute and Highland, rely heavily on tourism for employment and economic activity. This reliance on tourism supports local businesses, sustains jobs, and generates revenue; however, it also brings challenges, particularly in remote and sparsely populated areas where infrastructure often lags behind growing tourist demand.

The varied revenue patterns across the Highlands further highlight how tourism’s influence is uneven. Mainland regions like Highland and Argyll & Bute have shown promising revenue growth, while areas such as Orkney and the Outer Hebrides have faced declines, particularly with the investment in alternative sectors, such as energy. This diversification offers the potential for more sustainable economic growth and less reliance on tourism.

Moreover, the differences in tourism patterns between urban and rural regions highlight the different ways tourism supports both areas. Urban centers like Edinburgh and Glasgow attract more international tourists, benefiting from their higher spending and extended stays. Meanwhile, domestic tourists drive the tourist economy in rural areas where they seek non-serviced accommodations that align with local capacities and resource availability.

Ultimately, while tourism offers substantial economic benefits to the Highlands, strategic management is essential to balance growth with sustainability. This balance can help preserve the unique landscapes, local culture, and quality of life that make the Highlands so attractive to visitors in the first place, ensuring a stable future that respects both economic needs and environmental priorities.

Sources

DATA

~ All Maps and Charts created by Isabeaux Graham ~

Great Britain Boundary-Line, Ordnance Survey, September 2024. osdatahub.os.uk/downloads/open/BoundaryLine.

Industry Statistics, Scottish Government, October 2024. www.gov.scot/publications/industry-statistics/.

Local Authority Boundaries - Scotland, Spatial Hub, April 2019. data.spatialhub.scot/dataset/local_authority_boundaries-is.

OS Open Built Up Areas, Ordnance Survey, March 2024. osdatahub.os.uk/downloads/open/BuiltUpAreas.

Regions: Research and insights on regions across Scotland, VisitScotland, 2024. www.visitscotland.org/research-insights/regions.

IMAGES (order of appearance)

Queen Victoria on 'Fyvie' with John Brown at Balmoral, 1863, G.W.Wilson, Photograph, National Galleries. www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/63179.

Old Man of Storr, 2023, Unsplash. unsplash.com/s/photos/scottish-highlands.

Highland Cow, 2022, George Wheelhouse, Photograph. www.georgewheelhouse.com/post/highland-cattle-outer-hebrides.

Shetland Lighthouse, Getty Images. www.istockphoto.com/photo/shetland-lighthouse-3-gm508077035-45346808.

Kilchurn Castle, Tourist Trail. www.thetouristtrail.org/locations/scotland/argyll-bute/.

Shetland Islands, World Atlas. www.worldatlas.com/islands/shetland-islands.html.

Standing Stones in Isle of Lewis, Scotland.org. www.scotland.org/live-in-scotland/where-to-live-in-scotland/the-outer-hebrides.

Orkney Islands, VisitScotland. www.visitscotland.com/places-to-go/islands/orkney.

Glenfinnan Viaduct, 2021, Go Ahead Tours. www.goaheadtours.com/travel-blog/articles/scottish-highlands-travel-guide.

Orkney Islands. Licensed Photo by Google.

Shetland Ponies. North Link Ferries. www.northlinkferries.co.uk/your-holiday/guide-to-shetland/shetland-area-guide/shetland-ponies.

Outer Hebrides. Licensed Photo by Google.

Oban. Kraken Travel. kraken.travel/story/things-to-do-in-oban.

BACKGROUND

“Beside the Seaside.” Historic Environment Scotlad. 2024. www.historicenvironment.scot/archives-and-research/online-exhibitions/scotlands-coasts-and-waters/beside-the-seaside/#:~:text=In%20the%20late%2018th%20century,Scotland%20into%20a%20tourist%20destination.

"Economy." Argyll and Bute Council. 2018. www.argyll-bute.gov.uk/my-community/economy#:~:text=Argyll%20and%20Bute%20has%20relatively,employment%20in%20manufacturing%20and%20finance.

“Economy.” Orkney.com. 2024. www.orkney.com/life/live/economy.

Kennedy, Joseph. "Exploring Inverness’s Negative Impact on The Rest of The Highlands." The Highlands Times. July 2023. thehighlandtimes.com/exploring-invernesss-negative-impact-on-the-rest-of-the-highlands.

Kirikkaleli, Dervis, Kwaku Addai, and Rui Alexandre Castanho. "Energy productivity, financial stability, and environmental degradation in an Eastern European country: Evidence from novel Fourier approaches." Heliyon 9, no 7 (July 2023). www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405844023052817.

"Places to Go." VisitScotland. www.visitscotland.com/places-to-go/highlands.

"Renewables met 97% of Scotland's electricity demand in 2020." BBC. 25 March 2021. www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-56530424.

"Victoria's Visit." Digital NLS. digital.nls.uk/scotlandspages/timeline/1842.html#:~:text=For%20a%20British%20monarch%2C%20Queen,years%20after%20taking%20the%20throne